The Centers for Disease Control has reported on the cause of vaping illness nationwide--and it confirms my original theory: a chemical contaminant.

|

| Vitamin E acetate From Alibaba Market Website. |

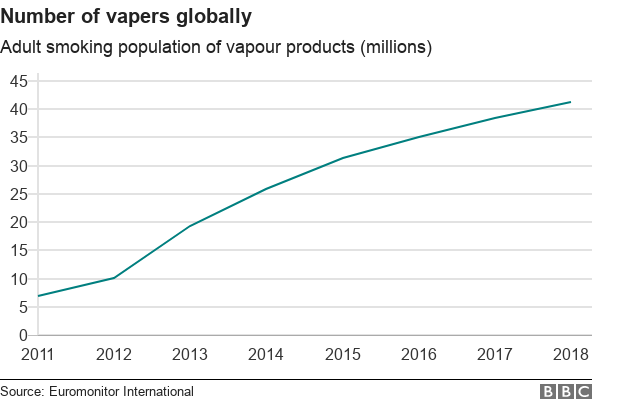

As I have mentioned previously, this is what happens in a market that is growing in an atmosphere of conflict between two sides. On one side you have free-market innovators aiming to make a buck and provide a low cost alternatives to tobacco use to people who either wish to quit smoking or to people who would like a safer alternative to nicotine use. Without any guidance or regulation, this vaping illness caused by a chemical made toxic by inhalation was bound to result.

I'm pretty sure that people cooking up new recipes for vape juices (like "Beer" and "Peanut Butter"--I mean really, who wants to inhale the flavor of beer?) aren't also looking to poison people to death. But absent leadership from health experts, researchers, and government agencies, what did you think was going to happen?

On the other side, you have these three players--health experts, researchers, government agencies--and basically all they have done is freak out about people getting addicted to nicotine, tried to ban flavorings, and aim to ban vaping outright. This is not productive, but it reveals the true character of many in the public health field who believe it is their right to legislate their idea of good health behavior.

|

Trump supporters expressing

their views on the prospect

of a vape-flavor ban.

From CNBC.com

|

As I have argued previously, nicotine is not itself especially harmful. Finding this information in official medical databases isn't easy but is possible, and this article from Forbes provides a nice summary. I have also argued that, despite the fact that vaping is not completely harmless (what is harmless? breathing clean air!) it is way less harmful than smoking. So for people trying to quit using tobacco, and for those who don't intend to quit but who would like to reduce their level of harm, it is a reasonable alternative (further research may modify my stance on this, but so far, so good).

Harm reduction is the approach to managing the instinctive human drive to seek pleasure, often from various substances such as drugs. Measures that would reduce harm in this case include a partnership between government and industry--including small-scale industry and not just Big Tobacco companies--to develop a list of safe ingredients for vape juices; enforced bans on both retail and internet sales of vaping products to young people (whether this ends up being 18 or 21 or somewhere in between); research that avoids the biases against nicotine, and against human pleasure; and perhaps a real conversation about how it is we wish to regulate adult behavior in pursuit of pleasure.

No matter how you feel about the President, he is paying attention to the wishes of a lot of ordinary people, and he seems to understand this libertarian streak, as the ban has been placed on hold for now. It is reasonable to ban behaviors that place the public at great risk, especially when that risk extends to people who don't wish to engage in a behavior but are affected by it. Think, the ban on civilian use of hand grenades, or tightly regulating highly addictive drugs like morphine that can be dangerous even to bystanders when mis-used.

It is reasonable to enforce a ban on children having access to dangerous products-of-pleasure, such as alcohol or the free use of motor vehicles. Kids need time to grow into effective decision-making. It is reasonable to require warnings, or training, or licensure for things that can wreck society around us. But it's not reasonable to pass rules that only satisfy a particular, scolding constituency, or create a more dangerous black market, or end up hampering a potentially harm-reducing phenomenon like vaping.

One might argue about the public health costs of vaping, but I would note that we don't yet know what the costs are and indeed, the benefits in reduced combustible tobacco use might outweigh the less costly harms of vaping. We just don't know yet, so why assume? Furthermore, we must admit that there are cultural and political dimensions that come with evaluating vaping, because these are the same dimensions that come with considerations of alcohol, tobacco, and now marijuana. On a scale of known harms, alcohol is more harmful than vaping, at least the preliminary evidence strongly suggests. We tried banning alcohol. See where that got us? We need a more honest discussion in our society about personal responsibility, community responsibility, and human nature. This discussion wouldn't focus on a "yes/no" or "us versus them" polarity. Rather, it should be willing to admit human prerogatives in a free society, the limitations of assigning a monetary value to every human decision, and the fact that people aren't perfect, not can we make their lives "perfect"--if we even know what that would be.

Sorry it was so long in writing--it's been a pretty busy semester--but Thanksgiving break has provided a window for me to catch up. So let's all give thanks at this giving time of year.

And now, I'm going to give my students their grades