Is this a thing?

I think so. I just now made up this term to describe what I'm seeing in my office these days. Back in September I proposed some ideas about post-recovery syndromes from actually having COVID-19. So far I have not seen very many people with physical problems after having COVID-19. The few I have seen seem to be doing mostly ok, but it's still early, since some have yet to return for a follow up visit.

This doesn't surprise me too much: Most folks don't think of alternative medicine to treat the sequel of a brand new disease. So stay tuned. I suspect I'll have more to say in the coming months.

What I am seeing a lot are cases of people who are ordinarily not depressed or especially anxious, suddenly displaying signs and symptoms of clinical depression and anxiety disorders. I'm seeing behavior and conduct disorders in kids who have been kept from other kids as their parents aim to protect the family from coronavirus infection.

I have been giving remedies for these disturbance, but not in all cases. This is because sometimes a basic "psychological hygiene" approach will address the problem. Lately I've been "prescribing" play dates for kids, establishing safer bubbles of friends and neighbors for respite and interaction, and even exercise as means of relieving the indefinite sense of pointlessness and boredom that have become a part of daily life for so many.

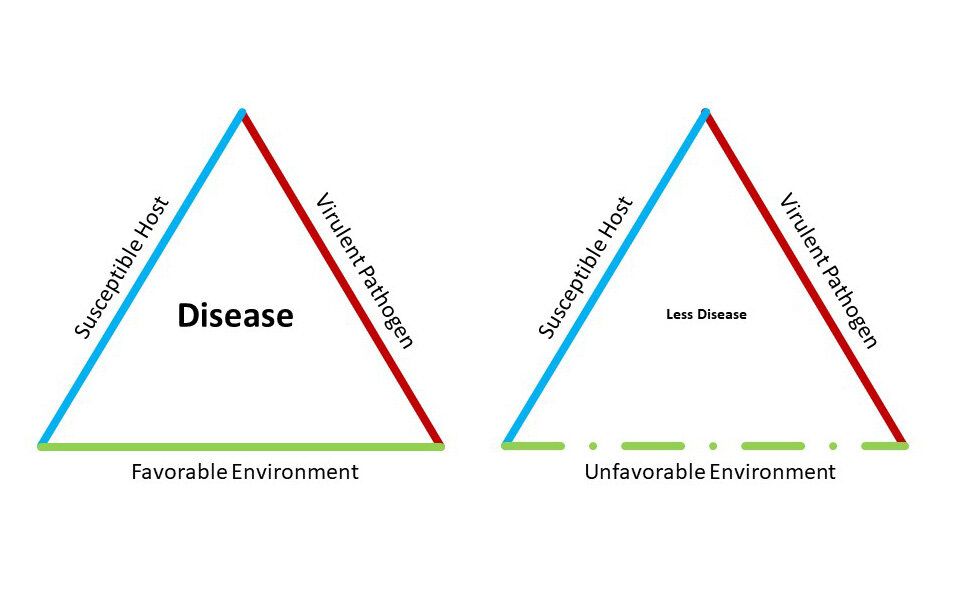

Remedies can heal a lot of problems, or at least help heal them, but some things are a matter of the environment. No matter how many great remedies a person takes, if he continues to smoke cigarettes, there's going to be some ongoing harm that can cause or aggravate disease. I can give a smoker Bryonia for a cough, but the cough will only improve a bit if the patient keeps engaging in the behavior that aggravated a cough in the first place!

I can give remedies for fatigue and weight problems, but if the person never engages in exercise and good nutrition, those remedies are only going to take him so far. Environment--both exterior and interior to the person--matters. The pandemic has created an environment of what I call an "ongoing toxic exposure" for many people. It's important to find ways to address our usual human needs. These don't change. We can be creative about how to address them, but that creativity can only go so far when we consider how human beings are wired and constructed.

For example, no number of Zoom play-dates will substitute for the need children have to physically and freely interact with their peers. Development just won't be the same if contact with other kids their own age is 2-dimenstional and structured through remote electronic contact. We end up with a choice: Am I more worried about a virus? Or the long term effects on my child's development of prolonged and indefinite lockdown?

I don't have a ready answer for that. Parents and people facing adult isolation have to navigate this for themselves. I can give developmental and psychiatric advice, but I can't resolve people's personal feelings, anxieties, and hopes with their moral or ethical mindsets. But I can at least specify the terms of the problem. We've been very focused on control of viral spread, but that is not the only thing at issue, and I thought that today I would share what I am seeing as a way to make the matter of choosing more understandable.

"Are you getting the vaccine?"

Homeopaths are kind of famous for rejecting immunization, and many view vaccines as a definite hazard to a person's health. Those of you who know me know that I do not.

Vaccines work, mostly. In a way they are themselves "homeopathic" in a sense (or technically, "isopathic") in that you're giving something that would in its natural state--a virus, bacteria--cause the disease we're trying to prevent. The published side effect profiles are generally pretty mild and catastrophic adverse events are rare. In homeopathic medical school we were presented with the idea that sometimes contact with a vaccine may lead to subtle or major health changes not on the published lists of side effects.

I find this plausible, and is also a statistical explanation for research that has failed to find specific diseases linked to specific vaccines, such as the lack of a statistical link between MMR vaccine and autism. In this way, even if MMR use isn't likely to lead to a higher risk of autism specifically (that we have proven), the proposal that any vaccines may lead to an increased risk any disease hasn't been studied. So we don't know.

So this leads some people to decide, "that risk, however small, isn't for me." They don't immunize. Others decide, "that risk is small enough, and the risk I feel for the actual disease the vaccine prevents is large enough, that I'm going to immunize." As we see: it's still a matter of choosing among different risks. It's no way to run a public health program, but it is a way to view one's own health, or the health of one's children one is responsible for.

I have covered the whole conversation about this in general elsewhere. Here I'll focus it on a possible coronavirus vaccine.

"Are going to get the vaccine?" My answer to this has been "I probably won't be first in line." I could be. As a health care worker, I'll certainly qualify. Why won't I be? If you go to my "Research" page on my website, you'll see I was involved with nearly three dozen drug trials in my time doing HIV medicine. One thing I learned from that and from my 30+ years in this business observing patients is that in post-marketing trials--that is, the observations we can make of people getting a product after it is licensed and in general use--is that numbers matter. Sometimes it takes a few hundred thousand uses to see weird side effects emerge.

Ok, but that means such side effects are statistically unlikely. Good. But I kind of want to know what those rare events are before I complete my personal "risk-to-benefit" equation. Most of the time vaccines don't seem to hurt people. There are times when the risk might be greater or lesser. As an example, a flu shot usually isn't a big deal, but I have observed that for people with systems in a delicate balance, or when they're on a new remedy for chronic conditions, it might be best to hold off on a vaccine for the moment, until their health is more stable.

It's a myth that little things are completely harmless. It is a law of Nature that anything added to a system will change that system in some way. It is also a law of Nature that you can never be sure that such a change will be trivial. Sometimes it isn't. We're all a bit different!

So will I get the vaccine? Maybe. But I think I'll sit back and observe the roll out for a while before I decide.

So in the meantime stay well, be peaceful, and do the best you can.

Happy Thanksgiving!