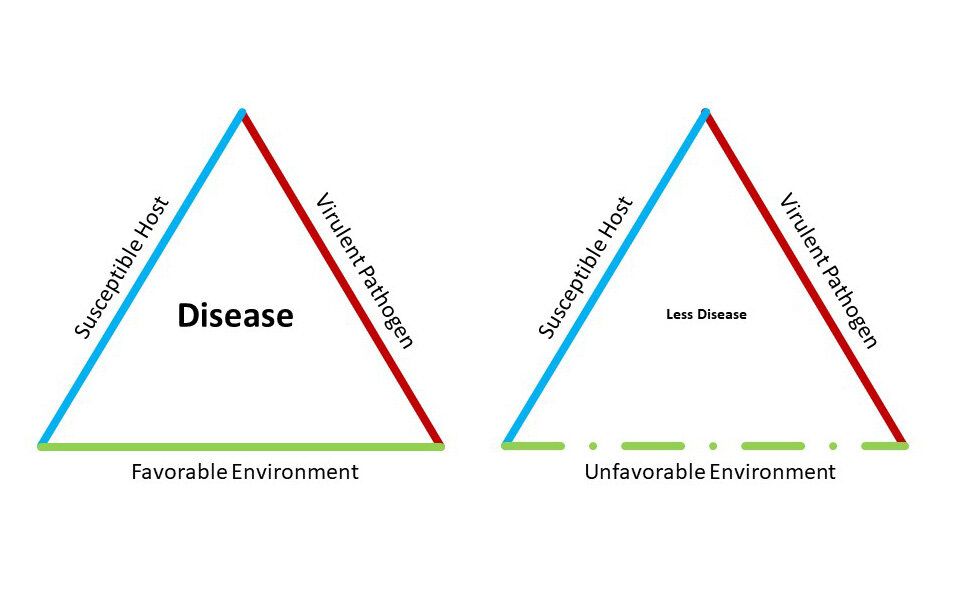

The epidemiologic triangle is a teaching device to help students think about the elements of infectious disease. The triangle on the left below, is the basic requirement for an epidemic. The one on the right is an example of how changing one part of the triangle can change the course of a potential epidemic and make it less likely, or at least less harmful to the populace.

This image is from Popular Mechanics, a science magazine online, and in it they discuss how the use of masks, physical distancing, isolation, disinfection--all things we've been asked to do--can create a less hospitable environment for the novel coronavirus, and thus "flatten the curve." That is, reduce the number of infections enough so that things don't climb off the charts and overwhelm our medical services.

| Our new friend. Artwork: Billboard.com |

In an article on Fivethirtyeight.com, Maggie Koerth discusses how "Every Decision Is A Risk. Every Risk Is A Decision." As we now emerge from our homes, we're trying to the calculate risk of everyday activities. Koerth details how much is controversial in risk estimation, and how we're learning from the science that is still evolving. But there are things we can estimate generally. I include the link for my readers to check out, because she also writes well about how individuals engage in such calculations.

For example, being at a gathering, outdoors, with maybe eight people you know well, and it's a sunny day...even if no one's wearing a mask, the risk is probably much lower than, say, going to a bar where you're shoulder to shoulder with any number of friends and strangers.

That's pretty straightforward, and it's intuitive. For some people, though, both prospects are equally "terrifying." What should be an easily guessed risk-difference actually has no difference to some people. Everything is equally (and possibly, maximally) risky. This is important, because as a society our own personal psychology becomes averaged into a kind of public mood. Individual estimates--whether scientifically valid or not--all go into our collective social estimation of risk, and that in turn further adjusts how we end up behaving socially. Each of us feeds that mood, and in turn the mood feeds back onto our behavior, which in turn feeds that mood and so on.

But it's not a cycle, more like a spiral. The process keeps changing with millions of individual adjustments that then alter the next moment in the cycle. This leads me to what was for me the most validating thing about Koerth's article: we're adapting. There may be a terrific vaccine around the corner. We may achieve herd immunity one day--either of these changing the host from "susceptible" to "non-susceptible." Or we may never find a decent, safe vaccine (I, for one, will not be lining up for the "first batch" of whatever soup that is--I've been personally involved in too many drug research studies!), and herd immunity may be years away.

Doesn't matter. I already see signs that people are, individually, beginning to adjust their personal risk calculus in terms that favor other things. How long can I go without visiting my elder parents? How long can my kid miss school? How long can I spin my wheels while my business withers? How long can I put off elective surgery? College? Other plans?

Eventually most of us will begin to reframe risk in broader terms that balance out other needs in our lives. This was true in the Flu Pandemic of 1918-19, and nothing about people has changed so much that this will not be the case today. It will be.

What Else Does the Triangle Tell Us?

Let me pivot to something that may give us a glimpse into this near-future: Host susceptibility.

When I was working with HIV patients earlier in my career, it certainly looked as if that virus was really deadly. The ravages of AIDS make COVID-19 look like a wimp. Yeah, COVID kills some, but AIDS killed everybody.

Or so we thought.

Turns out that once we had some drugs available, and we had some time to collect ourselves after losing so many bright lights (sons, daughters, Freddie Mercury, Robert Mapplethorpe, Arthur Ashe, Elizabeth Glaser...) to HIV, and after we had better technology to just understand a germ that was so much more novel than today's coronavirus, we learned that HIV was also subject to the Rule of the Triangle. HIV was not universally virulent and hosts were not universally susceptible.

It turns out that a small-ish fraction of people have genetic mutations in their immune systems that are mostly benign. These mutations may make them a little more prone to get pneumonia or the flu, but they make it really hard for HIV to get into people's immune cells. People who have both mutations (CCR5 and CXCR4) basically can't get HIV. This feature has even been turned to advantage in HIV drugs like Fuzeon.

I began to wonder about this a few months ago. Basically the thinking has been that all humans are susceptible to COVID. This has led to the belief among many that "If I get exposed to even one viral particle I might die." This is wrong for two reasons.

First, there's dose. We don't actually know what the "dose" of virus is that can lead to a full-blown infection. This is related partly to another aspect of our triangle: virulence. Because humans (and other creatures) are equipped with protective barriers (skin, mucus, little white blood cells that live in tissues), it usually takes more than one little tiny viral particle to get infected. This is being studied, but it's early yet, so we don't have a good sense of how much or how little virus it takes to bring on disease. There are articles out there on this, but the fact is, we just really don't know yet, because there are too many factors to to make study of this easy, and because the studies themselves are very technically difficult.

Second, there's susceptibility. This is a bit easier to guess at, and with time it will become easier to know, because the same approaches we used to study HIV can give us insights into who is more, or less, susceptible to COVID.

We come into the world with trillions of T-helper cells. These cells are by dint of evolution programmed with detectors for thousands of potential infections that live on Earth. When we're exposed to one of these diseases, a subset of T-cells programmed with that pattern begins to genetically transform themselves into even better detectors for that infection that then go after the infection with a vengeance. This is why it takes 7-10 days to get over a cold: it took your T-cells that long to read the new cold virus (they change often), make genetic adjustments, and then to bring in the rest of the players that come rushing in to rid the body of the infection.

Could it be that some of us are just better genetically equipped than others to resist cornonavirus? I found an article recently that suggested that this is the case. I include a link here because readers might find it as interesting as I did. It basically reminded me that Nature works in mysterious ways...but it still adheres to rules. In this not-yet-peer reviewed article from a research team in Sweden, we learn that maybe antibodies--whether from prior infection or a vaccine we have yet to invent--may be less important than something we're already carrying around inside us, the valiant T-cell!

Could it be that some of us are just better genetically equipped than others to resist cornonavirus? I found an article recently that suggested that this is the case. I include a link here because readers might find it as interesting as I did. It basically reminded me that Nature works in mysterious ways...but it still adheres to rules. In this not-yet-peer reviewed article from a research team in Sweden, we learn that maybe antibodies--whether from prior infection or a vaccine we have yet to invent--may be less important than something we're already carrying around inside us, the valiant T-cell!

Maybe some will find this reassuring. I do. In the flurry of "information" flooding our TVs, radios, Facebook feeds, and phones, I find it comforting to know that Nature still follows rules, and if we pay attention to those rules, perhaps we'll be able to better understand and apply our own personal risk calculations with less anxiety.

As always,

Be well!